"You haven’t succeeded in journalism if you’ve got a scoop by cheap and nasty means.”

From The Archive: An interview with Sir Harold Evans, February 2018

The Royal Auto-mobile Club was glossy, even preening - and I felt completely out of place. I was 17 years old, geeky and scruffy, with a tendency to hide behind my hair, sticking out by dint of accent: non Londoner!…

Harold ‘Harry’ Evans was someone I had wanted to interview from the moment I saw Attacking The Devil: Harold Evans And The Last Nazi War Crime. Curiosity can be selfish like that; in a what-the-hell-ask-the-question-anyway moment, I emailed his website. On the condition I read The Vanity Fair Diaries, a book by his wife, we’d be “poised for a more informed chat.”

I wanted nothing more in life than to sit at the feet of the story affront - a witness in action. ‘Journalist’ grants you a licence to be curious; legitimation for your natural character is impossible to say no to. He was as much my hero as my friend and editor; I miss him dearly.

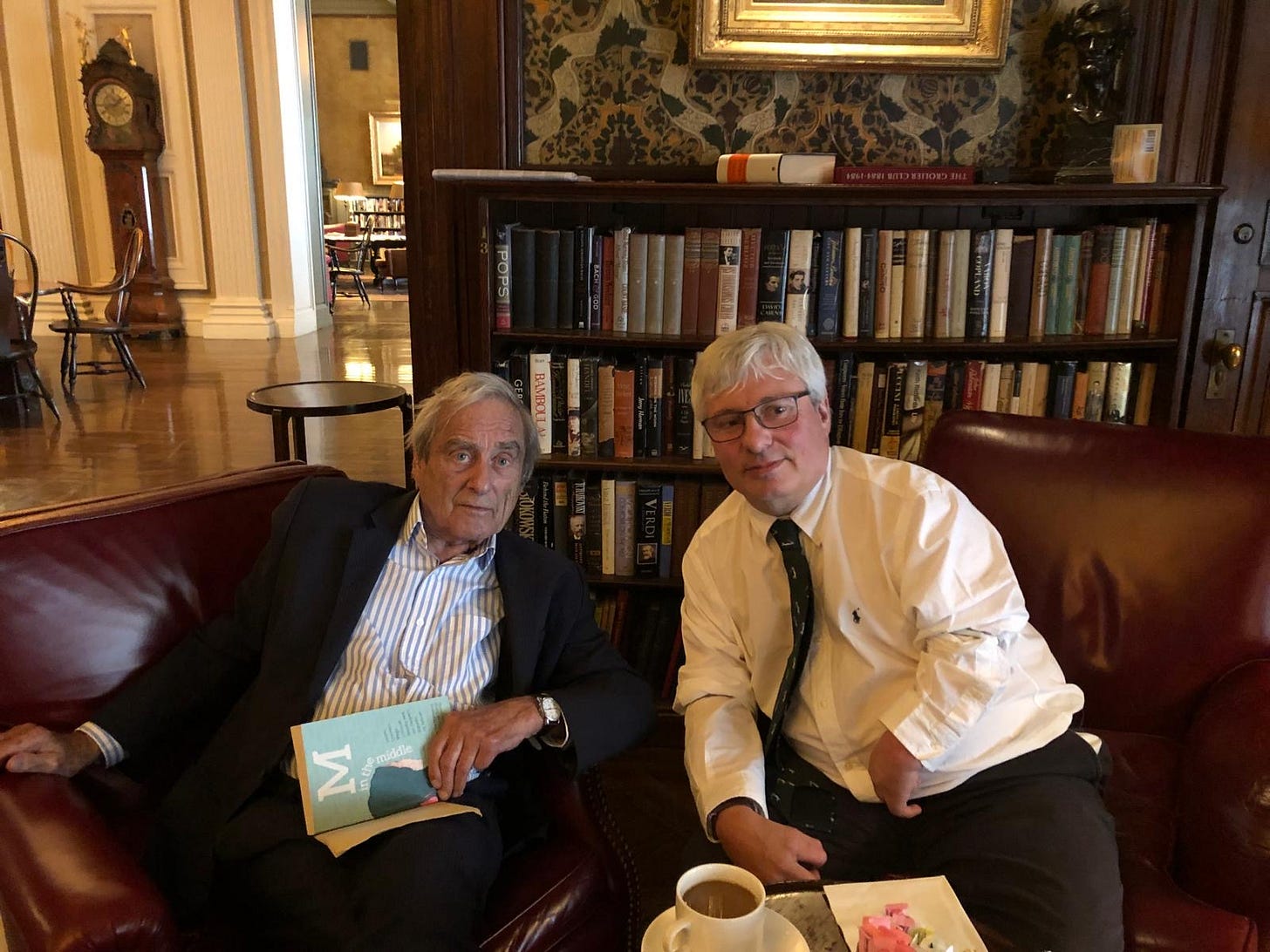

He died on this day in 2020; this photo shows a Thalidomide campaigner and survivor, Guy Tweedy, gifting a copy of a book and note I’d sent to Manhattan. Harry died 4 years ago today; this was the original interview I conducted, posted on the defunct site Byline.com on November 29th 2018. It has not aged well, the language both mawkish and inelegant, dated and aged.

But I’d like to tell you a story of allyship, how it is not a crime to care, and how a better world is possible. We just have to see it.

Sir Harold Evans (known to most people as Harry) edited The Sunday Times from 1967-1981, as well as The Northern Echo. During his Sunday Times editorship, the investigative unit, Insight, was expanded. In time, they broke stories such as Kim Philby (‘The third man’), the DC Airliner crash, and Thalidomide.

W.T.Stead was a previous Editor of The Northern Echo; he was quoted as saying: “What a glorious opportunity of attacking the devil, isn’t it?” It’s a quote used in part for Evans’ Netflix documentary: Attacking The Devil: Harold Evans and The Last Nazi War Crime.

When asked today, Evans says the ‘devil’ most worthwhile to attack was “….restrictive laws like the contempt (Of Court Act) , which you read about, which probably prevented many ill-things being ventilated for the public benefit.” as it led to the suppression of truth. Still the pugnacious editor when we meet in a London club, he admonishes “..greedy business people, like Distillers, interestingly an all-male board, deciding the fate of mothers and their children.”

Distillers was a liquor company, who were new to pharmaceuticals at the time. They sold Thalidomide under the name Distaval in 1959-61, as licensed by Chemie Grunenthal. Distaval was perscribed for mornining sickness, however it was not safe during pregnancy. It attacked the foetus; it would destroy the formation of arms, legs or hands. It would also damage organs, hearing, or sight. The British government at the time refuesed a public inquiry, leaving the parents of survivours to sue Distillers, who denied negligence. The Contempt Of Court Act also did not permit anything critical of Distillers to be published at the time; the families were left struggling into the seventies.

Evans, appointed editor of The Sunday Times in 1967, was impatient with what he saw as the neglect of the families who were affected. He tasked the investigative team, called Insight, to trace the roots of disaster. He latterly challenged Distillers and the Contempt law with a moral campaign demanding compensation on moral grounds.

He says it “stirs the same kind of anger in me as all the Republican senators meeting without a single woman present to discuss women’s health.”

As we continue to talk, it is clear he is still passionate about the type of reporting needed to uncover wrongdoing, thus holding wrongdoing to account.

Since Evans lead the investigative unit, Insight , a lot has changed. He is quick to stress that, “there is some very good investigative journalism going on.”, yet “it’s amazing to me how limited it is in its range.”

An American citizen, he is a fierce critic of the National Rifle Association, advocating gun control, verbally plotting what he would do as an editor: “I would pinpoint those Republicans who are holding up gun control, and what their connections are.”

Among the cluttering, clanging noise of the London club where we sit, his discourse begins to change to talking about inspiration for stories.

Cutting himself off, checking that I have read My Paperchase, his autobiography, he references how he campaigned for cervical cancer tests for women. “There’s a case where I read something like that, and then I think ‘Well, let’s investigate it. Why in the… Why aren’t there tests for cervical cancer?’ ”

Evans is an advocate for diversity in journalism, noting the advantages it could bring to investigative reporting.

Admitting there were too few women under his editorship at The Sunday Times, he says he caused “…displeasure by creating the first woman photo editor, because it was thought to be a male occupation. So, clearly today is nothing like as restrictive.”

Evans is most responsive when talking about how people on the autistic spectrum can be an asset to journalism.

“Most autistic people.. Asperger’s, for instance..(there) is a whole spectrum there between people with highly specialised skills, certain social inabilities which can be overcome.”

I smile at this, impressed. It leads him to talk about his son; his tone changes, becoming tender. “I have a son who is Asperger’s. And he is absolutely wonderful, one of (the) most kindest human beings.. So that’s on the emotional side, but on (the) intellectual side, he’s not very good at numbers, but is a GPS. He’s called Georgie -Georgie Positioning System.”

Digressing slightly, it’s revealed that Evans is on the board of The American Institute For Stuttering, as his son had a stutter when he was younger. To illustrate his point, he demonstrates how a stutterer would react to a difficult conversation that you or I may perceive as being something simple.

“And they get ignored, you know. Or they get, or somebody says ‘why, why don’t you speak more clearly?’ And the answer is the fault lies with the system.”

My next question is a bit personal, so I acknowledge that he may not wish to answer; has he ever wondered if he was on the Autistic spectrum?

“You think I’d be so lucky?”

I laugh, shocked at this. However, Evans admits to being obsessive. His PA also reveals that his son calls him “Mr OCD”.

Considering this further, Evans says: “But I’m certainly obsessive which is a disadvantage because I can’t let things go. It may be considered an advantage in journalism, that you want to get to the bottom of the story.”

The #MeToo and #TimesUp movement prove to be more controversial.

Condemning the alleged actions of Harvey Weinstein, to him the #MeToo movement is “..a desirable eruption of protest against the way women have been treated for many years, with various degrees of coercion and various degrees of consentuality .”

But he adds, in hoping it doesn’t get out of hand, that “due process and moderation” are needed.

Given that Tina Brown, his wife, runs The Women In The World Summit, I wondered if Evans would describe himself as a feminist. The answer was not what I was expecting: “Yes” he says.

“My wife is a heroine . Apart from being brilliant.. Have you read her book?”

Tina Brown has recently released The Vanity Fair Diaries, documenting her editing tenure at Vanity Fair, turning it from a failing publication to a cultural powerhouse. (I read this book as a prerequisite for the interview, not having just “looked at it”.)

Recounting an early inspiration from a Women In The World summit, Evans shared a memory that he’d never forget. Explaining how the second year of the conference, a missionary stood on stage, alongside another woman dressed in Tribal dress. The latter was describing how her daughter had been taken away for genital cutting (FGM), and had subsequently died from septicaemia. He noted her determination that it would not happen again.

“ .. But this woman talking, the mother, had to go to another village, about four, five miles away. And when she got back her (other) daughter was missing. The grandmother had taken her for genital cutting, and she died.”

He notes that the audience was in tears, including him.

“Tina, two years after, had on stage the head Tribesman of 5,000 villages.”

The same missionary from two years prior asked the question ’”Why do you allow this to go on in your villages when the (villagers) are at risk and they die?”

Harry impersonates an angry response to the question; incongruous to the surroundings of the London club where we are sit, it’s almost amusing, but I dare not laugh.

“I said to myself ’For Christ sakes, what have you done Tina? We’ve caused a Civil War here.’ And then when it was translated , what he was saying was wonderful. It said ‘We are ashamed. This is terrible what is being done. I have stopped it. We are going to stop it.’ ”

He also mentions how Brown invited the Liberian activist, Leymah Gbowee, to a summit. Subsequently she wrote a book, which won a Nobel Peace Prize. Mighty Be Our Powers was published in 2013.

His approach to women’s rights is reflected, almost mirrored, in the work of his wife: “I’m all for advancing women’s (rights) in fact women are still under-represented on boards and everything. But Tina’s concentrating on the human rights.”

As a journalist myself, I’m also curious as to what Evans’ advice for journalists today would be. His response reflects his views, seemingly, towards the Leveson enquiry, and the lack of ethics revealed in part one.

“Well, realise what journalism ought to be. So, you haven’t succeeded in journalism if you’ve got a scoop by cheap and nasty means, or made somebody’s life miserable without cause. I mean, look at half the tabloid gossip columnists. That’s not journalism, that’s scavenging.

“So, for journalists today, I would say first of all identify what journalism is for you, what are the objects of journalism. And the simple answer is the truth, but it’s very hard to define. Matthew Arnold was good on this: ‘Truth does not lie in the middle.’ On the one hand, Hitler was a maniac, on the other hand Germany needed a strong leader..”

“So I think, as a journalist, you know, respect the dignity, freedom in intelligence, of people you’re gonna be reporting on. And don’t make things up.”

The thing about meeting Harold Evans is that he has such a sense of history about him, leading to my final question: given his impressive achievements, how would he like to be remembered?

He clanks his teacup in his haste to answer: “What about I’m alive today?”

Gently admonished for the premature nature of my question, there’s laughter in response, and a wish to “not go upstairs” for the next thousand years. Yet, cut through the laughter, and there’s a meek quality. He answers seriously.

“I’d like to be remembered as Harry. The son of Frederick, the husband of Enid and Tina. The father of Georgie, Izzy, Ruth, Mike, and Kate.”